Kimberly Curiale

Irving School

Maywood, Illinois

2010

Irving School is located 13 miles west of Chicago in Maywood, Illinois. We are part of School District 89, which includes Maywood, Melrose Park, and Broadview. The 3-, 4-, and 5-year-old children of Irving’s prekindergarten classes reside throughout the district. The district has four preschool classes, both with a morning class and an afternoon class, with a total of 160 children. Of the 40 children at Irving School, 20 attend in the morning and another 20 attend in the afternoon. Seven of the morning children are girls, and 13 are boys. Five girls and 15 boys attend in the afternoon.

Ms. Kimberly Curiale is the Preschool for All coordinator and morning class teacher and Mrs. Lynn Morgan is the afternoon teacher. Both teachers work with Mrs. Trennace LeFlore, the instructional assistant, and share Ms. Vivianna Barajas, a bilingual teacher, with the other preschools.

Phase 1: Beginning the Project

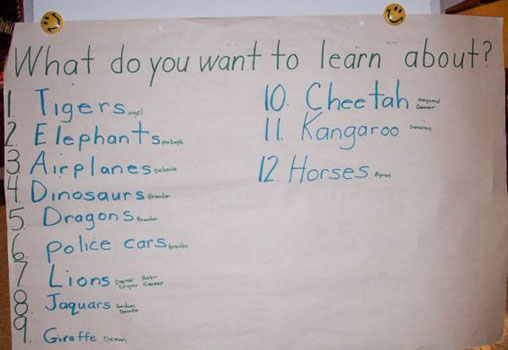

Earlier this school year, the children were very interested in trains. This interest continued with a project on airplanes that we called Up Up and Away. The project began in early February 2010 with a staff discussion about the various topics of study that seemed to interest the children. We looked over a child-generated list of possible topics (Figure 1).

From the list, the classroom’s instructional assistant chose her favorite topic (elephants), and I chose mine (airplanes). This gave the children two topics to choose from for their study. They voted, and our 6-week study on airplanes began!

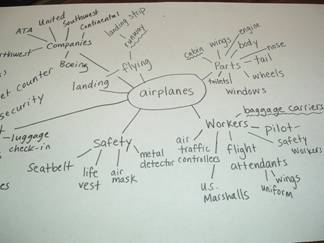

When the project was about to commence, the teachers got together and made an anticipatory web of possible subtopics that could deal with airplanes (Figure 2).

The teachers took small groups of children into the hallway to draw and have discussions about planes. We documented many of the conversations and events that took place. We created a web with the children and learned that they had minimal factual information about planes. For example, they thought that all planes crashed into the ground and that there were snakes that ride on a plane.

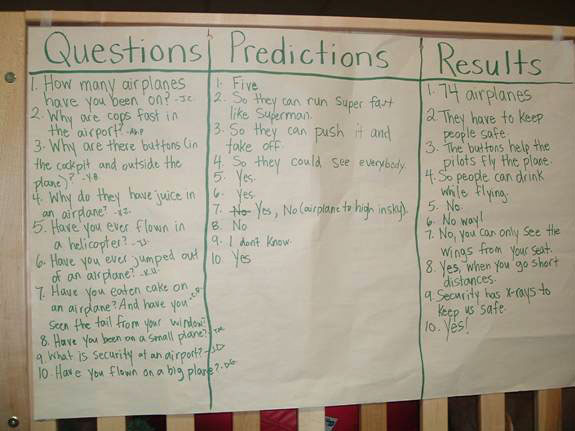

To begin generating a list of questions that reflected the children’s interest, the teachers started a discussion with the class about why all airplanes do not crash into the ground. Their initial questions centered on ideas related to skydiving but changed when they found out some classmates had been on an airplane. At that point, the questions became focused around what kinds of food you can eat on an airplane, what happens in an airport, who flies on planes, and why passengers fly. The questions were recorded on a trifold chart with the question, prediction, and, finally, the answer, which was recorded after our guest expert visited (Figure 3).

In the early phases of this project, the teachers predicted that the children would learn about the parts of an airplane and possibly connect this knowledge back to their earlier study of trains. We all thought they would create representational drawings and have some conversations about planes and show some interest in them. We had no idea this precursory information and interest would develop into the wealth of information, ideas, and activities that defined this project.

Phase 2: Developing the Project

As Phase 2 began, the teachers listened to the children’s conversations as they read and looked at books together, and they shared topic-related books with the whole group. We began to add topic-related items to the writing center, such as luggage tags and previously used airline tickets. We introduced models of airplanes that seat hundreds as well as others that seat fewer than 10 passengers. We integrated vocabulary terms that were new to the children, such as wings, tail, cockpit, pilot, passengers, and runway.

Unfortunately, because of security at the airports, we were unable to have any site visits. We spoke with every major airline, airplane manufacturer, and airport in the Chicago area and received the same message—No—from each one. We recruited our parent coordinator, Mrs. Tillmon, to serve as our guest expert, to come into the class and help answer questions about airplanes. Ms. Tillmon had been on over 70 airplane rides and was confident she could answer the questions our children would pose (Figure 4).

The children’s questions continued to develop over the course of this study. At first, they were primarily interested in crashing and falling from planes, but over the course of their study, their interest changed as they began to learn more about airplanes. At first, their background knowledge demonstrated their fascination with fictional tales that they had seen on television. They had viewed some movies that were not accurate representations of what it is like to fly on airplanes or what really occurs in airports and on airplanes on a daily basis. Once the children learned that some of their friends had been on airplane rides, the experienced classmates became the “teachers” and spoke at length about what transpired on their trips, what airports were like, and what they took with them on the airplane. For example, one boy had been on a cruise to the Caribbean the previous summer. When I asked him if he wanted to discuss his trip with his friends, his demeanor demonstrated how proud he was to talk about the topic. He sat up very straight and told his friends how his uncle took him and his mommy to the airport, and then they had to get on the big plane, and he was able to sleep on it! Then when they got off the plane, they had to get into another car, and that car took them to the ship. Then they discovered that there was an elevator on the ship!

As the facilitator, I sat back and listened to this boy tell his story, and I predicted what questions and outcomes would result from what he was saying. Right away, I started to think of how the children would probably develop interest in ships, elevators, or cars, as well as airplanes. To my surprise, every question the children asked dealt with their classmate’s trip on the airplane. They asked if he had food to eat on the airplane. Because he had mentioned that there were blankets and pillows on the plane, they wondered if there were beds, too. They were curious about where his mommy was when he was on the plane. They wanted to know if he actually flew the plane with the pilots and wondered if he got to press all the buttons.

As the project progressed, children expressed interest in how pilots fly planes, why there are different types of airplanes, why military planes look different from passenger planes, and how one person could fly on more than one airplane, as well as what kinds of food they offer you while you are there, what you do while in the air flying, and why there is security in the airports. When Ms. Tillmon arrived, she answered all their questions, and even prompted new explorations to begin (see Figures 3 & 4).

A few other children had been on airplanes prior to this investigation as well. When asked if they wanted to share their stories, one girl said she had just been to Mexico to visit her abuela (grandma) and then came back to Chicago and Maywood where we live. Another boy had just returned from a vacation to Mexico, but he missed grandma and didn’t want to talk about it.

An interesting side note about this conversation is that the girl who had been to Mexico is bilingual but would only speak to me in English. As I was reflecting on the documented conversation we had the one day, I noticed that every time she would reference Mexico, she would speak Spanish and every time she referenced Maywood, she spoke English. It was very interesting to see the differentiation and the “compartments” she was creating in her head about the differences between home and school. Consequently, after that, she would help with translating if I told her I was having difficulty understanding.

Four weeks into our project, one boy came in with a knowing smile on his face. He said, “Ms. Curiale, you will never guess where my daddy took me this weekend.” I assumed it would be Chuck E. Cheese or somewhere like that, but he was so excited, he could hardly wait to burst out, “He took me to the airport, and I saw lots of planes, and they were so big, and they were taking off, va-room into the air, and then we saw some sitting on the runway, and then we stopped at the gift shop, and LOOK!” He then pulled a model airplane out of his book bag. He was so excited to tell his friends about his adventure that his eyes just lit up when I told him I was excited for him to share his airport experiences with the class. They were all extremely quiet when he was telling them about his visit to the airport, and every child raised a question at the end.

One point worth noting is that one of the youngest children in the class (who tended to fidget frequently when the others were talking or listening to a story) had many questions through which all of his newly acquired vocabulary about airplanes came out. He asked, “Did you see the wings? The tail? The cockpit? The pilots? How about the wheels for the planes on the runway? What were the people wearing? Did the pilots have their uniforms on?” When his questions were all answered, he seemed content, got up, and asked if we could go play in the gym!

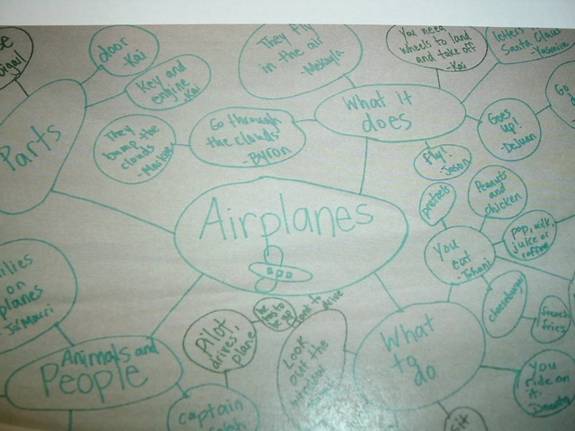

With the class, the teachers continued in Phase 2 by beginning a web of what the children knew about airplanes (Figure 5). We added to it over the weeks, as the children’s knowledge grew and changed the original schema on the topic. We used light blue the first time we webbed, green the second, and purple the third time. Using the three colors provided visual evidence that the children’s knowledge was increasing and developing over time as a result of the activities that the class engaged in.

Children took turns going outdoors with a teacher on a few days to count the number of airplanes in the sky. They went at intervals of 30 minutes, setting a timer each time, so each child would know when to stop playing at choice time and go outside. We took clipboards, graph paper, and a crayon and graphed the number of planes we saw as well (Figure 6).

The complexity of the children’s drawings continued to increase. At the beginning, their representations of planes would be shaped like a lower case t and would not have many details. The more we met in small groups to draw planes (in the hallway close to large windows), the more detail children added to their drawings of airplanes. Eventually some drawings included seats, windows, windows in the cockpit with pilots looking out, the tail and wings, wheels for landing, and the engine.

From drawing planes, we moved to constructing 3-dimensional models of airplanes (Figures 7 & 8). We had directions for creating a paper airplane. We looked at the pictures and tried to follow the directions as well as possible. When the children were done creating their planes, they wanted to fly them! Having too many obstacles in the classroom, we went into the hallway. Each child flew his or her plane and counted how many square tiles it flew over before landing. The children then created a graph representing the results of the experiment. They hypothesized that the reason some planes went farther than others was because those planes had been made with pointy noses and others had not. This hypothesis was tested again when Ms. Tillmon came and was asked the validity of it. She gave an explanation and agreed with the children that an airplane with a pointed nose could “cut through the air faster than a roundy nose on an airplane.”

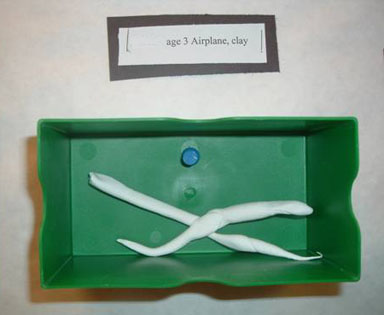

The class continued to model 3-dimensional airplanes using clay, wood, and papier-mâche (Figure 9). These models, along with the dramatized version of an airport and an airplane ride, transitioned us into the final phase of this project.

Phase 3: Concluding the Project

The culminating event that brought us to the conclusion of this project was our airplane party. We invited staff, friends, and families to join in and celebrate our learning (Figure 10). One of the children created a flier that we sent home to families “Pleas kum tq our arplaaaaaaaaaaaan prtee” and chose four clipart pictures to post as well.

Prior to the families coming, we posted all the artifacts and discussed everything with the children to help them remember what to tell their families. On the day of the party, the children each had a pointer to point to what they were explaining. When the families arrived at the school, they were greeted by the children shouting, “Welcome to the Airplane Party!” The visitors were told that it was the responsibility of each child to take his or her family around the classroom and to show them all the artifacts that represented the activities and ideas learned over the course of the 6-week project.

What a success! The children took their families, the school office staff and health clerk, and the district director of literacy around the classroom and demonstrated their individual understandings of everything that took place.

Some of the what the children (and teachers) gained from this project included new vocabulary; phonological awareness; math skills, including counting, graphing, spatial relationships, weight, and height (when building our 3D construction of an airplane); social and emotional growth through group projects and sharing materials and praise on a project; science concepts, including velocity (of airplanes into the air), recycling (materials for the construction), and collecting and recording data.

Teacher Reflection

Reflecting on this project, I realized how multifaceted project work truly is. The children used many different skills, including higher-level thinking skills as well as the basic skills that teachers are responsible for addressing with the 3- to 5-year olds we work with. Letters, numbers, sounds, and counting came to be a part of this project but so did graphing, analyzing, summarizing, and problem solving—all of which will aid in higher-level thinking strategies as the children become older.

I was surprised at the dynamics of this project. Every child was involved at some point, excited to explore or help a friend, and each child continued to make progress with growth and learning on his or her own terms. Projects lend themselves to differentiated instruction, because children who are functioning at higher levels of understanding will take different ideas and thoughts out of it than children who are functioning at other levels. For example, some children began copying words and would ask what they said (after the object was no longer in front of them), while others began writing words and sentences and took them home to read to their families.

Up Up and Away, a study of airplanes, was a very interesting topic for preschool-age children. Many times, the theme of transportation comes up in a classroom, but really taking the time to break the theme into a manageable project topic enabled deeper understanding and greater retention of knowledge to take place.

One child who particularly benefited from this experience was a 4-year-old boy who had been in our classroom since the previous school year. He was very shy and quiet last year, opening up a little more this year. He was not writing, rarely drew, and was exhibiting speech that raised concerns. Throughout the course of the 6 weeks of the project, he became so engrossed in the topic that he became the expert on drawing airplanes, especially when checking the details of others’ drawings. He would frequently remind other children to remember to add certain parts to their planes, and he would help others who felt they didn’t know how to draw an airplane.

If I were to do this project again, I would actually visit an airport on my own time and, if nothing else, try to pick up fliers or papers that I could bring back into the classroom. I would ask to take a few pictures, even though I was able to pull some off the Internet. If I knew in advance that my brother, a flight attendant, would have a layover or trip to Chicago, I would ask him to be the guest speaker. Unfortunately, over the course of this study, he was not in Chicago and was not available to speak with the children.