Deb Buckingham and Amy Ross

Pickwick Early Childhood Center

Ottumwa, Iowa

2022

The investigation of combines took place in a collaboration between Mrs. Buckingham’s and Mrs. Ross’s two preschool classes of children at the Pickwick Early Childhood Center. We had 20 students who attended all day. Pickwick serves 3- and 4-year-old children at no cost Monday through Thursday. The program is funded through a collaboration of the Iowa Voluntary Preschool Program and Iowa Head Start. The project began in October and lasted about six weeks.

Phase 1: Beginning the Project

Our project began with plans to do a project based on autumn. We hoped to incorporate the Tree Study from Creative Curriculum. We predicted this focus would allow us to talk about environmental changes with the children. As part of the preparation for the study, Deb videotaped her husband harvesting corn. As the children watched the video, one asked, “Where do combines come from?” That question brought a new focus to the project.

To build interest in the topic, Deb brought in a part of a combine, a corn-head snout (see Figure 1). We asked the children to guess what it might be, draw it, and write about it.

We teachers expected we would simply have a short project. We had no idea it was going to explode into the dynamic and ongoing learning experience that it became. It turned out that the students were very interested and proceeded to push us out of our comfort zone.

As our initial exploration and discussion came to a close, the children were interested in continuing to learn more about combines. So we gathered their questions about aspects that they wanted to investigate. Related topics, such as snow, also appeared. They were an inquisitive group, and when one person mentioned snow, the discussion began to include winter. We wrote the questions on our interactive board so we could refer to them throughout the project.

- Where do they get sprayers?

- Where do worms go in the winter?

- What does the tractor do with snow?

- Where do snakes go in snow?

- Where do farm worms go in the winter?

- Where do we get cows?

- Where do we put cows in the winter?

- Where do pigs go when it is snowing?

Phase 2: Developing the Project

As our investigation of combines deepened, we used the Internet to see different kinds of combines and the crops they could harvest, including pumpkins, cotton, carrots, soybeans, and corn. Children would ask a question in circle time as we read books or as they were playing, and that would become an opportunity to find new information. If a particularly interesting fact was discovered, it was shared with the entire class when we convened our circle time. For example, no one knew there were harvesters for pumpkins, so a video of them being picked in a field was shared with everyone, and the teachers learned from it, too.

Our guest expert, a farmer named Mr. Buckingham, greatly enriched our project. For example, he was able to join us on speaker phone when we had questions, and he sent us information about tractors and combines and parts of tractors and combines to explore (see Figure 2). He also loaned us tools, a steering wheel, an oil can, and lots of corn to shell. The steering wheel became an integral part of choice time, with everyone taking turns “steering” around the room. Chairs were sometimes set up, and the driver would navigate an imaginary tractor or combine through a field. The large wrenches and screwdrivers he provided were used to “fix” the shelves in our classroom and were also a prop to carry in jean pockets.

In the meantime, we added a toy combine and tractor to the block area. The children did observational drawings of the combine (see Figure 3), and they used it to “harvest” pieces of plastic corn. It was an extremely popular item. The combine and tractor were first displayed during choice time to introduce them to the class, and the children could choose to draw them if they wanted.

Our field site visit was to an implement dealer. The managers gave us permission to explore all the tractors, combines, and other equipment. The children were able to (carefully) touch and climb on the equipment, and they were free to experience everything until their curiosity was satisfied (see Figure 4). We had planned to do drawings on the field trip, but unfortunately the teacher managed to leave school without the clipboards. One of the students from Mrs. Ross’s class lived on a farm and served as an expert as the children strolled through the equipment. Everyone had a turn to sit in a combine tire—experiencing its huge size—and to sit on a small tractor.

At the conclusion of the visit, we interviewed the owner with a list of questions we had developed at school. Most of the questions were about the colors of the implements, how tires were changed, and whether there are any super combines. The children theorized that all red combines were super.

Seeing and experiencing the actual machinery piqued the children’s interest even more, so following our trip, the investigation took on increased energy when we discussed how we could show what we had learned. At first the children decided to build a combine. Then someone said a tractor, so we voted on it: tractor, combine, or both. The children voted that they would like to build a combine and a tractor. They then dictated a list of materials they would need for their construction, and we began to collect them.

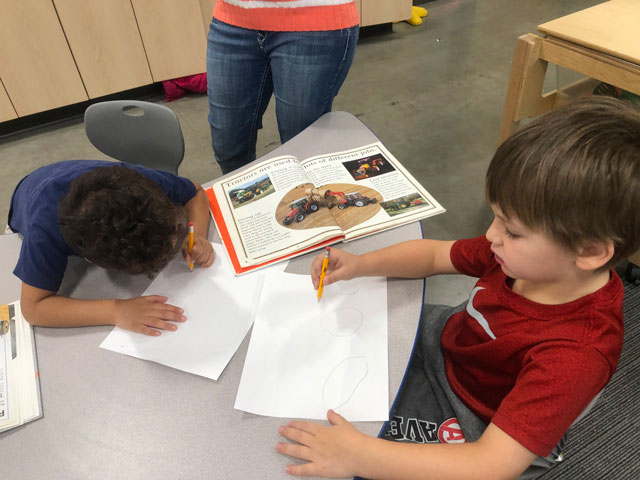

To support the children’s research, we ordered many books from the local area education agency, which provides support to school districts in its region. We read them to the children, and the children browsed through them independently to get ideas about what to build and how to build it. The children were intense researchers. Using the books and our experiences, they drew plans that revealed what they wanted to build (see Figure 5).

Ultimately, the children built a combine and a tractor. To support this process, we put out all of the construction materials we had collected and told the children to use their ideas to put the combine together. Rarely have I seen children work so intently. The classroom, which is usually quite loud, had a quiet buzz of activity. Everyone worked on a part of the combine or tractor and contributed to the final product (see Figure 6).

All students, no matter their academic or social skills, were involved. Some spent their entire choice time working on it, while others put in just a few minutes. They were so focused that most of the combine and tractor were built during a single hour and a half of choice time. More final details were added over the next few days.

Phase 3: Concluding the Project

Once they were completed (see Figure 7), the teachers helped the children work together to make labels for the parts of the combine and tractor. In addition, to help families appreciate what we had been doing throughout the project, we displayed a series of photos during parent-teacher conferences. We also video recorded each child talking about the project and shared each child’s video in a parent portfolio.

Teacher Reflection

Our investigation about combines and harvests was meaningful for several reasons. First, children in our part of Iowa would often see tractors and combines operating in fields, but because they are city dwellers, they knew little about them. Second, many of the children have relatives who were or are farmers, but they really did not know much about farming or the machinery used by farmers. Finally, we have a John Deere plant in town where several of their family members work.

The biggest benefit of the project was that the students became researchers through books, videos, and experiences. As they completed the project, they used their social skills in the areas of cooperation and persistence as they worked together to complete the project. They have carried those skills into the subsequent topics we have studied and have become more intentional as they create and plan.

We have done projects before and have been impressed with the children’s learning, but this really excited us. We have always believed that preschoolers are capable of being intense learners, but we were overjoyed to see that in action. Although this was not a topic we had originally planned to explore, it became one of our favorite topics.

The most meaningful moment for us was watching the intensity and concentration the children used while creating their combine. Our early childhood teacher’s hearts were inspired by how much they were invested in the project. It made us want to provide them with more opportunities for deeper exploration.

One of our students with ADHD has difficulty focusing on anything for even a few seconds. This project allowed him to be an explorer and also a leader in ways he had not been able to be in other class learning experiences. The carryover for him has shown in his ability to plan and create. He has channeled his role as explorer and leader into new avenues with art and loose parts. We do not think he would have tried these activities without his experience in constructing the combine.

If we were to do this project over, we don’t think there is a lot we would do differently. We would definitely trust the students to show us the road map of what to learn. We learned that we can trust them to determine what is important to study.