Jacqueline Nepola

Second Grade

St. Matthew Elementary School

Cedar Rapids, Iowa

2020

The Voting Project took place during October and November 2020 as many of the children’s family members were engaged in discussions about the upcoming election. Twenty-five second graders and their teacher were engaged in this three-week investigation of the meaning and procedures for voting. The project took place despite challenges presented by the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, guest experts were not allowed in the classroom, and students were not allowed to work with partners or small groups for any significant length of time.

Phase 1: Beginning the Project

The students were interested in the upcoming 2020 election, and they frequently mentioned the names of national and local candidates. Two members of my family work as poll workers, so I knew I would have access to guest experts the children could interview. Given the interest of the children and my resources, I decided to start the project in coordination with a unit on government that is part of our regular second-grade curriculum. I was unsure at the beginning what the final outcome of the project could be, but I hoped that students would be able to hold some kind of election. While students had studied the executive branch of government in social studies, they had not had direct instruction on the election process.

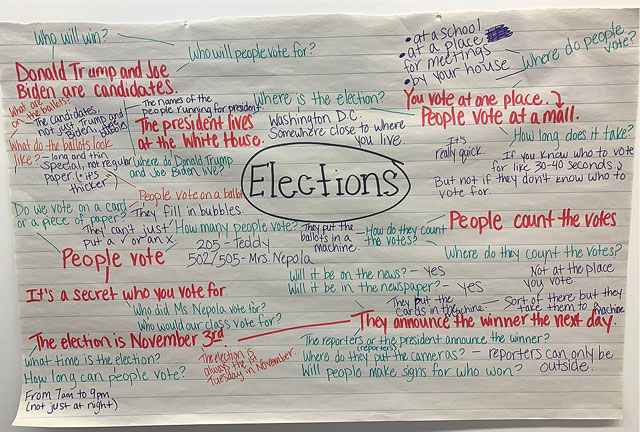

On October 29, I opened the project by asking the students to brainstorm what they knew. Then we read Grace for President by Kelly DiPucchio and recorded what we learned. I used a red marker to record their beginning knowledge on a web. We also made vocabulary cards for the words election, nominate, and candidate that day.

The following day we read Duck for President by Doreen Cronin and added a vocabulary card for the word ballot. I suggested to students that we hold our own election and asked who we could nominate for candidates. Students suggested teachers or classmates, but we ruled that out after I explained why feelings might get hurt. It was interesting to me that they did not bring up holding an election for the actual candidates. I suggested the children nominate book characters because they would be candidates that the students were familiar with. The students agreed and started excitedly announcing who they would nominate. They wrote down which character they wanted to nominate and why in their notebooks (see Figure 1). On November 2, I recorded the questions the students had about the election on our web in teal.

Phase 2: Developing the Project

On November 4, we conducted a zoom meeting with two poll workers, and the students asked them the questions that had been recorded in teal on the web. The answers to their questions were recorded on the web in purple.

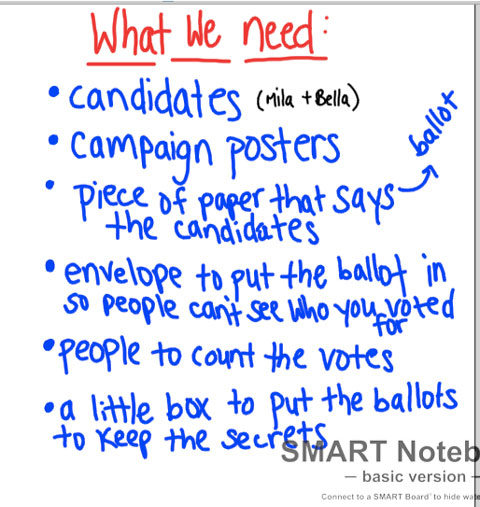

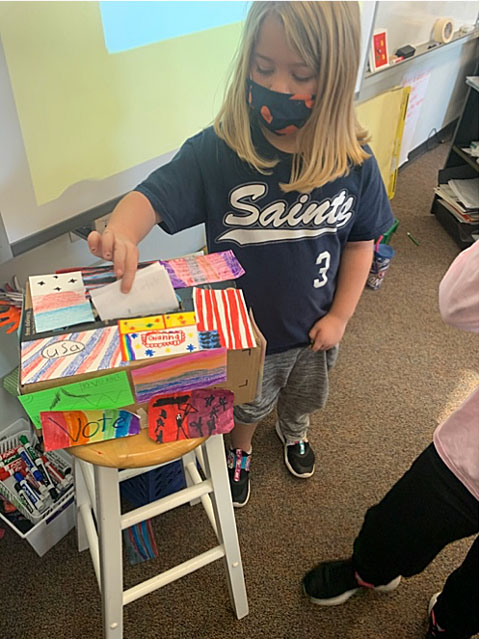

Next, students generated a list of tasks we would need to complete before we could hold our election (see Figure 2), and some students asked to do particular jobs. One important item they listed was “a little box to put the ballots in to keep the secrets.” On November 6, I brought three boxes for students to choose from. They chose a box that was slightly larger than a shoebox. They determined that the first step was to tape the box closed. Then two students drew a rectangle on the box to show me where to cut a hole in the box. After the hole was added, students discussed whether it was large enough and tested their theory by folding a piece of paper and sliding it through the hole.

While some students worked on the voting box, two others walked around the classroom with pieces of paper and asked their peers to write down which book character they wanted to nominate. As the list developed, a student noted that “someone already wrote [my character], so I’m just going to put a tally mark.” Other students followed suit.

Students also decided the ballot box needed to be decorated. There was a lot of discussion (i.e., arguing) about who would get to draw the decorations. I asked if there was a way they could all contribute. They first suggested the idea of passing the ballot box around, but I reminded them we could not do that because of social distancing requirements. As an alternative, I suggested they each draw something that could be attached to the box, and I gave them each a notecard to decorate. They chose to attach the cards with tape, rather than glue, and this led to the problem of pictures falling off throughout the week.

On the same day, another student was nominated to create a ballot by writing down the names of all the candidates. She decided to use half-sheets of paper for the ballots because “smaller papers will fit in the ballot box better.”

By November 6, some students were becoming concerned that every student would just vote for the candidate they nominated. I asked the students who should be allowed to vote in our election. A discussion ensued in which students debated whether the whole school should be allowed to vote. Some objected because “not everyone [e.g., the kindergartners] will know who they [the characters] are.” I then asked the students who would know the characters, and they decided the third-grade students would know because “they had Ms. Nepola as a teacher last year, so they will know the books.” I asked how students could persuade people to vote for their candidates. Many students suggested signs, so some students began to make them for their candidates. One student came up with the idea of putting his campaign sign on his locker in the hallway, and others followed suit (see Figure 3).

On November 9, the students decided that we would need to make badges for the third graders that said “I voted.” They asked for more notecards and cut them in half to make the badges. Four students were chosen to deliver the ballots and the ballot box to the third graders.

On November 10, I distributed the ballots to the students. It was interesting that some of them stood up folders on their desks while they completed their ballot for “privacy.” I had laminated the “I voted” badges, and after each student voted, I passed them a badge. Students asked for tape to attach them to their shirts (or their heads).

I consulted with the third-grade teachers, and we selected a time for their students to vote. Pairs of students delivered the ballots to each classroom. They explained to the third graders that they needed to fill in the bubble next to the character they wanted to vote for and to only vote for one candidate. Once the third graders had used their ballots to vote, my second graders gave the third-grade teachers the “I voted” badges for distribution and returned to our classroom.

Phase 3: Concluding the Project

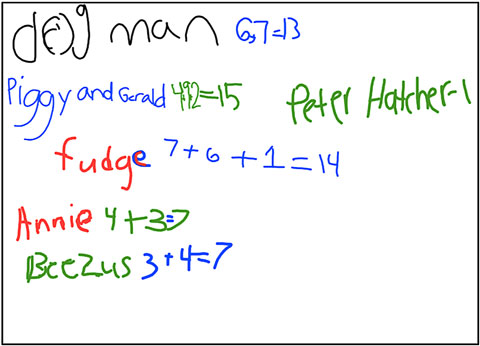

On November 11 we discussed how to count the ballots. All the students wanted to be involved. One student came up with the idea of giving each student ballots so they could “put all the votes for one person in piles.” I distributed handfuls of votes to about half the students who then sorted them by vote. The other half of the class then counted each vote, while some recorded the number of votes on the Smartboard.

Piggy and Gerald won the election, and two new pairs of students were selected to be “news reporters” and go to the third-grade classrooms to report the results of the election. Before they left, a classmate wrote down the vote count for them “in case the third graders ask how many votes they got” (see Figure 5).

The final web (see Figure 6) indicates the growth of student learning about the voting process. Red type indicates what they knew at the beginning of the project, and orange type indicates what they knew after reading Grace for President. The students’ questions were recorded in teal, and purple indicates what they learned after talking with the guest experts.

Teacher Reflection

I found the most challenging part of implementing the Project Approach to be the documentation. Being the sole classroom teacher and having multiple facets of the project going on at once, I often missed opportunities to take pictures or catch what students were saying. I often jotted down notes or quotes from students on my lesson plans right after the lessons. Later I copied them into a notebook to keep them all in one place.

Another difficulty I had was letting go of control. In the future, I will be sure to let students write more on our class web and vocabulary cards. Without the constraints of the pandemic restrictions, I look forward to meeting with my class on the carpet and keeping these things in places that are more physically accessible to students.

It was exciting to see my students participate in this project. I enjoyed giving them a voice and choices in their learning experience. Students were clearly excited and invested in this project. They would ask each day if we were working on our project that day.

They showed a good understanding of the vocabulary words taught and were able to explain them in their own words, rather than repeating a rote definition. They also used them regularly when talking with each other. This showed me that they truly understood the words and what they represented.

In the difficult days of COVID-19, when opportunities for partner and group work were scarce, it was great to provide students with opportunities to have meaningful interactions with each other. Even though students had to largely remain in their seats and work on parts of the project individually, the social interaction and collaboration was hugely beneficial to students’ emotional health.