Kim Burd and Laura De Luca

J. L. Hensey Elementary School

Washington, IL District #50

2014

The Worm Project took place in morning and afternoon sessions of two self-contained ECE classrooms in the J. L. Hensey Elementary School in Washington, Illinois, a community of about 15,000 near Peoria. Head teachers in the classrooms were Mrs. Kim Burd and Mrs. Laura De Luca. Each had a teaching assistant for morning and afternoon sessions. Between the two classrooms, 15 children ages 3 to 4 attended the morning session and another 15 children ages 4 to 6 participated in the afternoon. All children had individualized education plans (IEPs).

The curriculum for both sessions in both classrooms is generally play-based and experiential in nature and is guided by the children’s interests and IEP goals. By the time the classes began the study of worms, the children had experience with several prior investigations and were familiar with discussing, making observations, sketching, and webbing. The investigation of worms lasted about three to four weeks.

Phase 1: Beginning the Project

During several days of spring rains, worms made their way to the school blacktop. One particular morning when the children arrived and got off the bus, they stopped in their tracks when they noticed the multitude of worms that had come out during the rains. The children were excited and full of comments about the worms throughout their breakfast routines. After breakfast, the class returned outside for more investigations.

Children participated in the initial exploration at varying levels. Some watched intently and made comments to their classmates and the teachers, while others began to pick up and gather worms. Some of them threw worms into puddles and dug in the dirt. Children who were reluctant to touch the worms used sticks to pick them up or touch them.

By the end of the first day, the teachers brought worms indoors to investigate at tables. The children remained engaged and curious, and the teachers recorded their comments and observations. Some children attempted to draw the worms (see Figure 1).

The teachers found many opportunities for vocabulary and language development throughout the worm project (see Figure 2).

The enthusiasm was “catching”, and soon the principal, Mr. Sharp, came in to see what the children were learning (see Figure 3).

Through observation and discussions with the children during the first day, several questions began to emerge that would guide the beginning of the worm investigation.

- Why did the worms come out?

- Where did the worms come from?

- Do they like water?

- Do they like dirt?

- Do they swim?

- Do they bite?

- Is that poop?

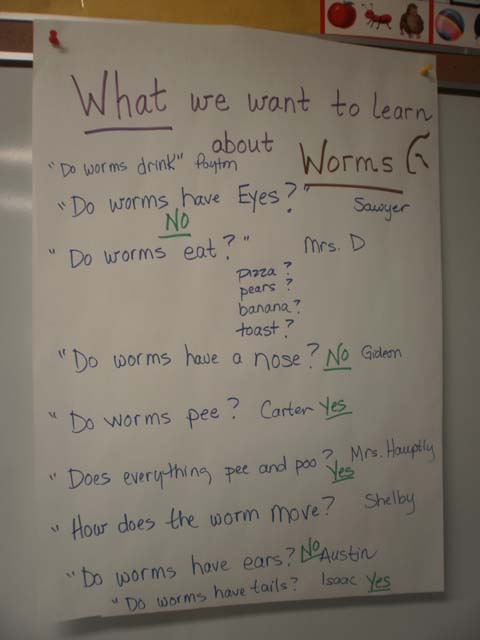

During the first week of exploration, the children in the older (afternoon) class met to chart a list of “What We Want to Learn about Worms” to post in the classroom (see Figure 4). The children revisited the chart several times during their investigation.

Phase 2: Developing the Project

The teachers provided a variety of experiences over the next few weeks that helped the children deepen their understanding and answer their questions about worms. Activities were designed to provide sensory interactions and exploration for children at all levels of ability. During this phase, the children were engaged in touching and feeling the worms, looking closely at them, watching their movement, and discussing what they observed.

Compost worm farm

The children wanted to save the worms in the classroom, so we used books and the Internet to see how to do that. Mrs. Burd brought in a large, clear bin to create a compost worm farm. Children were able to articulate that the “farm” needed dirt. From the books and online resources, the children learned that they needed to add things such as food scraps, egg shells, and moisture to the dirt to keep the worms alive. The worms also would need darkness. Children helped maintain the farm daily, and it was readily available for activities and experiments.

Worm Observation Bottles

One of the first Phase 2 activities provided the children a chance to see what worms do underground. The children helped to fill 2-liter bottles with earth and “goodies” from the compost farm and covered them with black paper sleeves to create darkness (see Figure 6). The bottles were placed in the classroom science centers for independent research during center time. The bottles were left covered at night, and the classes would check for tunnels the next day.

At the science centers, children were able to investigate the worms’ movements, the tunnels they made, and other features of worm life (see Figure 7).

The children explored the worms and touched them when they were ready to do so (see Figure 8).

Many of the children who initially hesitated to touch the worms grew more confident about it as they became more familiar with the worms (see Figure 9).

Measuring and comparing worms

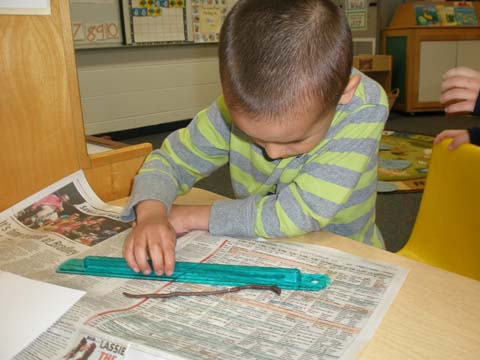

Kyle (age 5) asked one day to “measure them.” (For more about Kyle’s engagement with the project, see Teachers’ Reflections below.) The teachers provided rulers and drawing utensils, and children took up the task of seeing how big and how small worms can be (see Figures 10–11). They discovered that a worm’s length can change as it moves!

Wiggle Watching

The children had a variety of opportunities to observe worm movement. After watching them move on the ground and in the tunnels, some of the younger children explored worm movement on their bellies. They imitated the movement of worms by crawling through the classroom tunnel (see Figure 12).

Paper Towel Experiment

Some of the older children performed an experiment to learn about worms and water. Worms were placed in the middle of a paper towel that was dry on one half and wet on the other. The children made predictions about which half the worms would prefer, then observed the worms to see which way they would move (see Figures 13–14).

Wondering and Research

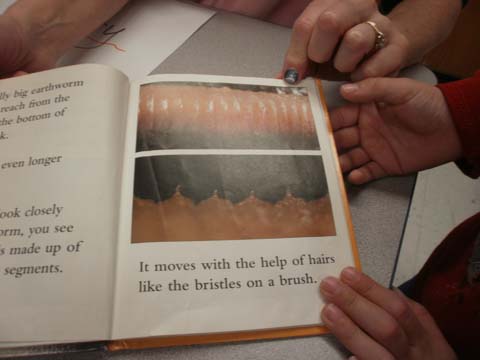

Throughout the project, the children were interested in finding more information about worms from the computer, books, pictures, and videos.

Sally (age 4.9), one of the project leaders in Mrs. De Luca’s room, spent a great deal of time observing worms on her own during choice time. Figure 15 shows her at the computer, where she worked with the teacher to verbalize observations and look up answers to some questions about the worms she had been observing at the science table (seen on the mirrored tray in front of her).

The teachers brought in storybooks and informational books to share with the children, placing them in the science areas and in the regular “book time” library areas. Teachers modeled interest in and use of these books to find information, and they read aloud to the children from informational text as appropriate (see Figure 16).

The children also watched several videos related to worms, including Worm Farm by Kevin. The teachers also showed a variety of YouTube clips about worms.

For the illustrated “Words About Worms” vocabulary chart (see Figure 17), the teachers selected words from research they and the children had done, printed them digitally, and placed them in areas where children were doing worm investigations. The older children who attended in the afternoon were able to use the words during their regular journal/writing time.

Sensory play

The teachers provided a range of opportunities for children to investigate and play out their ideas in sensory play. These activities included mixing dirt and mud, making representations of worms and their tunnels with fingerpaint, and playing with a variety of toy worms in the sensory table.

Phase 3: Concluding the Project

As children gained more knowledge about worms, they began to make a variety of representations to share what they had learned. Some worked individually, making worms from playdough, drawing them, or painting them at the easel. Other children participated in ongoing group work on worm-related creations.

Building a Worm Environment

Several children decided to create a worm “home” for the rubber worms in one of the sensory tables. They dictated a list of things that would be found in a worm’s world and, over several days, worked at building (and rebuilding) tunnels, making holes in the ground, creating grass and dirt and water areas, and adding trees complete with nests and birds, which, they learned, may eat worms (see Figures 21–22).

The Paper Worm

Several children collaborated to make a large worm from butcher paper to represent some of the things they had learned about worms (see Figure 23). The worm and the story of the project work were displayed in the hallway at school through the end of the school year.

Teacher Reflection

We share this project to show how children of all ages and stages of development can participate in project-based learning. The depth of investigation is somewhat different for each child, but understanding also deepened for each child through meaningful experiences during a project. We have found that all children feel like competent learners when their observations, ideas, and sense of wonder are valued and treated as important. This topic became a shared interest for almost everyone in the classes and made us close as a community of learners excited about the same thing.

Challenges

We encountered some challenges during the worm project related to time and scheduling, working with multiple classes, accommodating children’s varying abilities, and helping them become close observers.

Time and Scheduling: Time is always a challenge in our classrooms. We must coordinate all classroom activities with children’s therapy schedules and other unforeseen obstacles. During the project, we allowed time for children to continue activities over several days and had to “respark” children’s engagement with the topic with new materials on occasion.

Multiple Classes: Attempting to carry out project work with multiple classes also presented a challenge. With four unique groups of children in two different classrooms, it could be difficult to share in all of the experiences. Again, we found that allowing more time for continued investigations enabled children to rotate to different activities and come back to the ones that most interested them. We used photos and videos to revisit favorite activities and help the children share with each other.

Children’s Varying Abilities: For us as teachers, careful planning was important to allowing children at all levels of ability to participate in the worm project. Sensory activities such as mixing mud or fingerpainting worm tunnels were good for the younger children or those with more significant learning challenges, while other children were able to measure worms, help construct a worm model, or find answers to research questions on the computer.

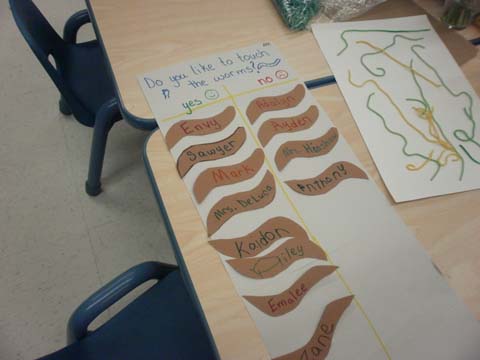

Teaching Observation Skills: We try to practice project observation and investigation throughout our routines from the beginning of our time with the children. Especially with our younger children or those with significant learning challenges, we value “the teachable moment” and make a “big deal” of calling children’s attention to the little things in our day, such as a spider on the wall or the clouds in the sky. As children are able, we teach them to ask each other survey questions and record the responses using yes/no T charts (see Figure 24).

We also encourage them to communicate through drawing. It is important for children who have little drawing experience or who have fine-motor challenges to gain confidence in their ability to represent what they have observed by drawing it. We have found that it is helpful if the teachers model what is involved in drawing and give children many opportunities to practice.

In support of project work, we integrate other skills and activities into our curriculum, such as representational play (“Let’s be spiders!”), book and computer research (“Let’s look it up!”), class webbing and charting, observation walks, journaling, and photo documentation.

We love to see the children “notice” the world around them, like little detectives. May they always keep this sense of wonder!

Worms Bring Out Kyle and Amy

We share the stories of two children as part of our reflection in a celebration of the benefits that we believe the Project Approach has had for our children with special needs and in the Worm Project for Kyle and Amy specifically.

Kyle’s Story

Kyle came to us at age 3. On his first day, he would not enter the classroom unless his mom was holding him, and he had his blanket in hand. He had a sweet smile for his classmates that day, but he would not interact with them. On Day 2 he walked in the side door of the school without his mom but cried at the separation. We encouraged him to investigate the toys and activities in the classroom at his own pace. On Day 3 he kissed his mom goodbye at the door and walked down the hall to our classroom. He mainly played behind the train table, but he did watch his classmates and later began to eat breakfast with us. By Day 10, Kyle was riding the bus and happily investigating the classroom, but he was not yet verbally communicating his wants and needs.

By age 4, Kyle was following the classroom schedules and routines; however, his understanding of language was progressing slowly. He needed a lot of support to understand directions and expectations.

The morning we discovered the worms on the playground was a happy day for Kyle. During our observations, he began to ask us questions about the worms. Kyle had not been asking or answering questions with meaning or purpose until this day. He even asked to measure the worms—bringing tears to his teacher’s eyes! Before that, we did not think he knew what measuring meant.

Kyle began to ask for materials to use when investigating the worms without prompting or cueing. He invited his friends to “play” with the worms. He laughed and joked about things he thought were funny about worms. He wanted to take the worms home to “teach” his mom about them. The worms were meaningful to Kyle, and he made some good progress on his IEP goals during the worm project.

Amy’s Story

Amy is a 3-year-old child with autism. She is mostly nonverbal and exhibits many behaviors that are associated with moderate autism. When the worm project began, she had been with us three months. We struggled to provide her with a secure, predictable schedule and help her communicate her needs. During choice making and play, Amy seemed to be “in her own world” most of the time. She had several favorite activities, such as lining up small animals, watching fish swim, and piling small toys. Teachers and peers would try to play near her, and the teachers intentionally tried to enter her play to help her build play skills, but she rarely engaged willingly with others.

During the worm investigation, Amy was focused on the actions of the worms. She picked them up, carried them, handed them to us, and mostly intently watched them (see Figure 27).

For days, she stopped on the way from the bus to look for worms and sometimes was angry if they were not out that day. She listened as we talked about how to touch, feel, and look at the worms. She could sit at the table (previously very hard for her) for long periods with peers, just observing the worms. During this time, Amy’s vocalizations, initiation of interaction, and eye contact increased. She was an active learner with her peers. Her attention was lengthened and her world was widened a bit. It was as if, for this topic, for this time, we shared our worlds. Amy continued throughout the school year to build on these shared experiences as her trust and interest in her teachers and peers grew. We really felt that this project had an impact on that pivotal moment in Amy’s learning.