Sarah Pappas

Madison Early Childhood Center

Elmhurst, IL

2021

The Squirrel Project took place in an early childhood center that serves students ages 3–5 through morning and afternoon sessions. Program funding is provided by the local school district, statewide Preschool for All, and tuition. Of the 26 students who participated, six had Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) and five were dual language learners.

All students had prior experience with the Project Approach. All staff at the center have been participating in extensive Project Approach training for the past three years, and teachers have shifted their instruction to primarily project-based learning. The squirrel project lasted six weeks. Teachers involved were Sarah Pappas, Colleen Hohman, Sarah Makinney, and Doreen Comings (speech and language pathologist).

Phase 1: Beginning the Project

Schoolwide, the teachers, instructional coach, and the principal selected eight overarching topics to teach over the course of two years. We began the process by sharing all of the “themes” we usually taught, and then we worked together to categorize them into broader topics. All students learned about one overarching topic at the same time. However, all teachers selected a more specific subtopic to focus on based on student interest. We had a goal for teachers to start around the same time. Most projects lasted six to eight weeks. After their projects, they did “miniprojects” or themes until we were planning, as a school, to move into the next topic. These miniprojects lasted around three to four weeks.

The overarching topic we started with was “animals.” To narrow the focus for our project, I carefully listened to students’ conversations and asked guiding questions to identify a topic.

One day we were talking about our favorite animals. The students took turns sharing a reason why a particular animal was their favorite. One student said, “My favorite animal is squirrels. I see them in my backyard!” Several students immediately shared that they also see squirrels in their yards and “even running on my fence!”

The next day, I placed a stuffed toy squirrel in our classroom library. Upon arrival, the students immediately noticed the squirrel and were very excited to take him around our classroom and engage him in their play. The following day I placed the squirrel at the art center and asked the students to draw a picture of a squirrel and describe for me what they know about squirrels. Next, I asked the students to share everything that they already know about squirrels, and we used their knowledge to create a topic web about squirrels.

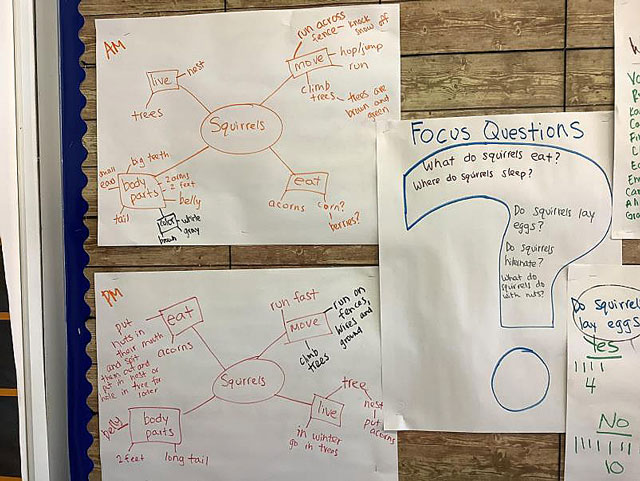

After several years of using the Project Approach, I have noticed that during topic webbing, misconceptions and questions often arise simultaneously. Consequently, as we webbed, I had our “question catcher” next to the web. The students are familiar with this anchor chart in the shape of a question where we record their questions. For example, as the students shared what they knew about squirrels and we recorded it on our web, a few questions also came up. One student in the afternoon class said, “Squirrels hatch from eggs!” And another student promptly responded, “No, they don’t!” So I said, “This sounds like a question we have: Do squirrels hatch from eggs?” I recorded the question on the question catcher.

As we continued on with our web, there were also some conflicting ideas about what squirrels do with their nuts. One student said, “They put them in their mouth and take them to their nest and then save them for later,” and other students thought they “just eat the nuts.” We decided to also add “What do squirrels do with their nuts?” to our question catcher. The next day, we reviewed the topic web and the question catcher. I asked the students if they had any other questions about squirrels. They had lots of wonderful questions! I recorded all of their questions and then later categorized and grouped them and came up with focus questions to help narrow our research (see Figure 1):

- Do squirrels hibernate?

- What do squirrels eat?

- Where do squirrels sleep?

- What do squirrels do with their nuts?

- Do squirrels hatch from eggs?

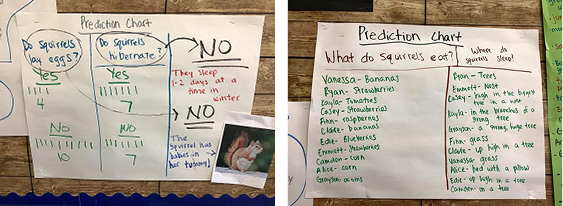

The following day, the students made predictions in response to their questions, and I recorded their ideas on our predictions chart. These student predictions allowed me to understand their knowledge base at the beginning of the project and increased their interest and motivation in engaging in the research (see Figure 2).

My expectations for the project were that the students’ interest level would continue to build as they learned more about squirrels. I was happy that their initial interest level was high despite limitations of the school year related to social distancing and COVID restrictions. We had some students learning from home remotely, and we weren’t able to go on any field trips. Because squirrels are observable from our school and from the children’s homes, I was excited that we would still have plenty of opportunities for field work and that all students could actively participate whether from home or at school.

Phase 2: Developing the Project

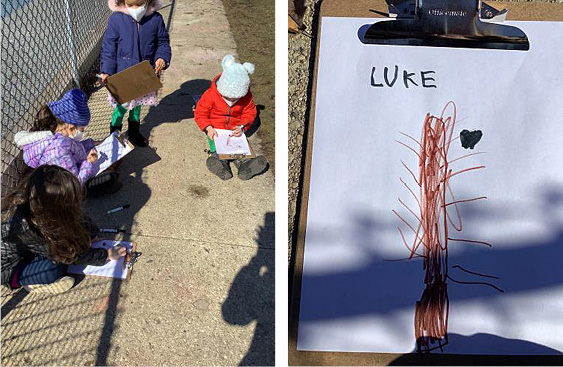

To begin our investigation, I gathered several nonfiction and fiction texts about squirrels, and we began reading them to learn more. The students were constantly asking me and other teachers in the room to read to them about squirrels. Gray Squirrels by G.G. Lake and Those Darn Squirrels by Adam Rubin, a nonfiction book, taught us that squirrels make nests using leaves, sticks, and squirrel spit. The students were fascinated by this. There is a large nest in a tree next to our playground. One of the classes last year did a project on trees, so we asked the children in that class what type of nest it was, and they told us, “It’s a squirrel nest!” We observed the nest, and the class sat outside and made observational drawings of the nest in the tree (see Figure 3).

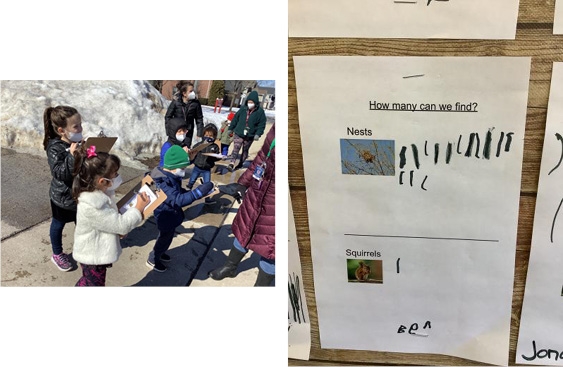

The students wondered, “Are there more nests by the school?” So we walked around the block. Because it was the end of winter and approaching spring, all of the neighborhood trees were bare. In Elmhurst we have lots of old, tall trees surrounding our school. All of the students carried clipboards on our walk so they could tally how many nests and squirrels they found. During our walk, we only observed one squirrel, and we found more than seven nests, which caused the students to wonder: “Where are all the squirrels?” (see Figure 4)

After we returned from our walk, we created a tally sheet of our observations of squirrels and nuts. We used this activity to spark a discussion related to our question: “Do squirrels hibernate?” The discussion began after our walk. The students realized that we only saw one squirrel and wondered “where are the squirrels?” I then asked them guiding questions such as “Do you think we will see more squirrels once it gets warmer outside?” When we first started walking around the neighborhood, it was about 40–50 degrees, so I asked them, “Where do you think the squirrels go when it is cold? How do they keep warm?” We watched additional videos and read more books to learn how squirrels keep warm and what they do during winter.

As the weather got warmer, the students noticed more squirrels running around the school. One particular day, it was colder and rainy again, and a student said, “The squirrels are probably back in their nests.” The students were very motivated to do research to find out the answers to their questions about what squirrels eat and their hibernation patterns. To support their research, I found a couple of YouTube videos that provided child-friendly information about squirrels. One video helped the students learn that squirrels do not hibernate, but they sleep for one to two days at a time during the winter and then come out to find the nuts that they had hidden.

To represent their learning, the students worked together to make three-dimensional representations of trees, nests, and squirrels. I initiated this activity by making trees on the walls of the classrooms, and the students decided to add nests and squirrels. They used the information they read in books and their observations from the nests in the trees outside to determine where to place their nests in the trees, making sure to securely place each nest on a branch that was “way up high” and near the trunk so “it was sturdy.” We left open-ended, three-dimensional art materials in the art center, and I prompted them with, “I wonder if you could use these materials to make your own squirrels” (see Figure 5).

Families got involved in the Squirrel Project. I reached out to them and encouraged them to help their child look for squirrels and squirrel nests around their neighborhoods. Several families sent me pictures of squirrel nests, and I printed them so the kids could share their findings with the class.

Through the window of our classroom, we could see a home with a fence. The students said they had often seen squirrels climbing fences. One student had an idea to make a fence on our window and thought that maybe it would trick the squirrels so they would come closer to our window. We then made binoculars so we could look for squirrels through the window. The students worked together to design the fence, and they hung it along the windows of our classroom (see Figure 6). They made signs that said “Squirrel Watching,” and they would often stand by the windows with their binoculars and watch for squirrels (see Figure 7).

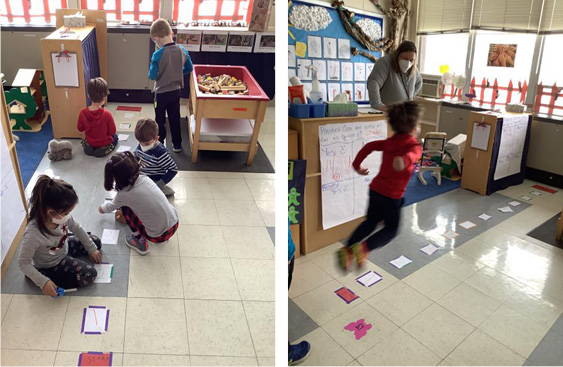

In one video they viewed, the students learned that squirrels can jump 10 feet. They were very intrigued by that fact and questioned, “Can we jump 10 feet, too?” I asked them to predict whether they could jump 10 feet like a squirrel. The next day, we worked together to create a ruler on the ground in our classroom that was 10 feet long. The students made the start sign and measured and marked the distance. They then got to see whether they could actually jump 10 feet. A majority of the kids jumped 3–5 feet on our ruler. They recorded their results below their predictions and realized that jumping 10 feet is pretty far—and hard! (see Figure 8)

At our easel, I posted pictures of squirrels, trees, and nests, and I made green, brown, and black paint available. The students really got interested in painting trees and nests, and they painted the most beautiful, detailed pictures to share their new knowledge (see Figure 9).

Because of COVID limitations, we were not able to go on field trips, but we did continue walks around our school’s neighborhood to look for squirrels and nests. The students predicted that as the weather got warmer, we would see more squirrels because they would not be sleeping so much. As we walked around on the day of our culminating event, they were so excited to see more squirrels.

One of the teachers in our class knows a squirrel expert who volunteers at the Oaken Acres Wildlife Center. At the center, they rescue squirrels and other wildlife and had recently rescued eight baby squirrels that weighed 20 grams each when they were admitted. We got to view a video of the staff at Oaken feeding the baby squirrels. The students loved watching the baby squirrels and took an interest in seeing their growth over time.

We continued to watch more videos of the baby squirrels growing and being taken care of at Oaken Acres. The students learned from the videos and also from reading nonfiction books that squirrels do not hatch from eggs but that they grow in a mom’s tummy. They also learned that squirrels are blind when they are born and they usually live in the nest for 1–2 months after they are born. I shared the videos on Seesaw so their parents could also watch them with their children at home. I encouraged them to follow Oaken Acres on Facebook so their children could continue learning, even after the project ended.

During our investigation the students also learned that not only do squirrels sleep in nests, they also sleep and live in dens and burrows. I placed natural materials (e.g., sticks and tree bark pieces, small toy squirrels, and acorns) in the sensory table, and the students became very interested in building burrows and dens for the squirrels to live in (see Figure 10).

We continued to provide materials that would help the students answer the focus questions from our question catcher. Through books and videos, the students learned that squirrels eat flowers, fruits, and insects in addition to acorns. We watched several videos that shared the importance of squirrels collecting nuts and other food and burying the food to save for winter. The students continued to ask questions such as “how do they find food when it is snowing outside?”

As the investigation continued, we checked back on our web and our question catcher to be sure we had done research to answer all of our questions. We recorded the students’ learning next to the question catcher and also on our prediction charts as we continued to develop our Project History Board.

Phase 3: Concluding the Project

Before the Squirrel Project, the class did an author study on Ezra Jack Keats. To end our author study, the students voted on their favorite Ezra Jack Keats story, and we made props and did a “Reader’s Theatre.” As we were approaching the end of our squirrel investigation, I said to the class, “Wow, you all have learned so much about squirrels. You are becoming squirrel experts! How are we going to share everything you have learned?” One of the students in the afternoon class responded, “We should write a book and have a squirrel play, just like we did for Ezra Jack Keats. We can paint the backdrop and pretend to be squirrels to show what we learned!”

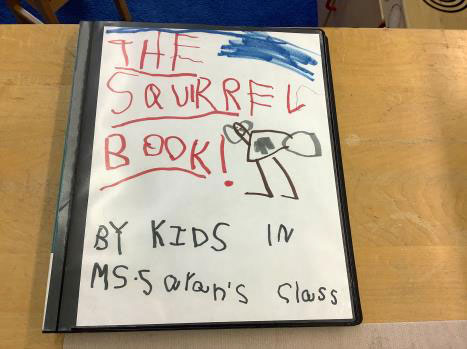

We took this great idea and ran with it. The class decided that we first had to write a squirrel book. One of the students said, “We can be the authors and the illustrators!” They worked together, and everyone drew pictures of what they learned and described their picture as the teacher wrote their words (see Figure 11).

Next, the students worked together to paint backdrops for our squirrel play so that it looked as if we “were in the woods.” They painted murals with big trees, nests, dens, burrows, dirt, and grass. We then read through the class story and prepared additional props based on what they wrote. For example, one student said that squirrels eat strawberries, so we got strawberries from the dramatic play center so we could use them during our play. Another student said squirrels run on fences. They decided they needed to add a fence to the backdrop. Another student added that squirrels jump 10 feet, so we added a ruler to our backdrop with numbers 1 through 10 (see Figure 12).

A couple of students worked together to make a title page for our story. We read through the book several times before our play to make sure we had prepared everything we needed. The students had a great idea to wear squirrel colors on the day of the play, so I reached out to parents and asked their help to pick out squirrel-colored clothes (e.g., gray, brown, black, or red).

We performed our play for each other in two groups (see Figure 13); we had a group of actors and a group of audience members, along with a narrator. We switched roles and did the play twice so everyone had a turn to take on the various roles. One of the teachers recorded videos and pictures so we could share our play and our learning with families through Seesaw.

At the end of the play, I gave all of the students a copy of our class squirrel book to take home along with a “Squirrel Expert” certificate to acknowledge all of the hard work. They were very proud of their certificates. I reminded them to read their squirrel book at home and share their learning with their families, friends, and neighbors.

Teacher Reflection

Reflecting on this project, I feel very proud of my students. They certainly taught me that even during a pandemic, when we had limitations placed on us and just a challenging year in general, one thing remained the same: Children are curious and they love to learn. It was such a wonderful distraction to fully engage in this project with them and focus on learning and growing together. Squirrels ended up being a great topic because they are relatable and observable for all of my students.

This project was especially meaningful for me because the student in the very beginning who said that squirrels were his favorite animal was a student who I was really trying to get more engaged in his learning and trying to strengthen his interactions with his peers. It was powerful to see his engagement and excitement during this project. During our culminating event, he worked very hard and cooperated with his peers on making a nest to hang in the tree. His peers enjoyed learning with him, and I felt as if it truly helped build a stronger culture in our classroom.