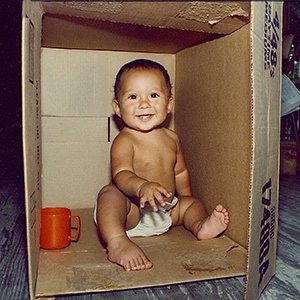

Every year since 1998, one or more toys or games have been inducted into the National Toy Hall of Fame. Located in Rochester, New York, the Toy Hall of Fame is a partner with the Strong National Museum of Play and several related organizations. Inductees have included Lincoln Logs, the Raggedy Ann doll, GI Joe action figures, the Atari 2600 game system, the rubber ducky, and the game of Monopoly. The winners tend to be items with a long history of popularity with children. I was pleased to see that commercial products aren’t the only things that can be inducted. Hall-of-Famers also include the blanket (2011), the stick (2008), and in 2005, the cardboard box, the subject of this blog post.

Generations of children have played with cardboard boxes. Many families have stories along the lines of “We got him [name of a popular toy], but he liked the box better.” A child can turn a box into a nest, a tunnel, a castle, a robot costume, a space shuttle, a garage for toy cars. … The list goes on and on. The picture book Not a Box by Antoinette Portis humorously shows many imaginative uses for a cardboard box.

Cardboard boxes certainly inspire pretend play, but they may also be the least expensive early childhood STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) toys around. If you have had small children or worked with them, you’ve probably seen how boxes allow young children to explore questions and problems related to force and motion, properties of matter, and structural design.

Let’s consider some cardboard box activities related to force and motion:

- Trying to move a box while sitting in it.

- Pushing or pulling a box across a variety of surfaces (tile floor, carpet, wood, sand, sidewalk, snow, ice).

- Moving a box (with or without a load) down or up an incline.

- Rolling balls or wheels down ramps and pathways made of boxes or parts of boxes.

- Applying pressure to different parts of a box (side, corner, etc.) to see how they “hold up.”

Children have discovered properties of matter by

- trying to cut cardboard;

- trying to play with cardboard that has been leaned on, bent, cut, or folded and creased;

- comparing boxes made of various types of cardboard, such as corrugated cardboard, folding boxboard; and

- seeing what happens to cardboard when it gets wet and when wet cardboard dries out again.

Young children also have explored principles and practices of engineering design in different ways:

- Using boxes as construction materials: How high can we stack them before they fall over? How can we position them so they don’t fall? How might we alter a box to make a doll house, a racetrack, a doll cradle, a costume, a car?

- Investigating boxes as structures: What shapes and sizes do boxes come in? How big does a cardboard box have to be to hold five counting bears, five stuffed animals, or five children? What are some ways to strengthen a flimsy or broken box?

After observing children’s STEM-related play with boxes, a teacher might involve families by sending each child home with a shoebox or similar cardboard box and a list of suggested play activities. Parents are bombarded with commercial messages urging them to spend a lot of money on playthings: “Buy this toy to help your child be smarter! Buy this stuff that goes with that toy!” They may appreciate the reassurance that they can promote a child’s learning with an item that has earned a place in the Toy Hall of Fame but can easily be replaced at no additional cost—or recycled when the child’s interest has faded.

Jean Mendoza

Jean Mendoza holds a Ph.D. in curriculum and instruction from University of Illinois, a master’s degree in early childhood education from the University of Illinois, and a master’s in counseling psychology from Adler University of Chicago. She served on the faculty of the early childhood teacher education program at Millikin University and worked with children and families for more than 25 years as a teacher, social worker, and counselor. She recently collaborated with Dr. Debbie Reese on a young people’s adaptation of An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States (by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz). Her long-standing interest in children’s literature is reflected in her reviews of children’s books with Native content, which have appeared in A Broken Flute and on the blog American Indians in Children’s Literature. Jean and her late husband, Durango, have four grown children and six grandchildren. She lives in Urbana, Illinois.

Biography current as of 2021

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Durango Mendoza for photograph of child.

IEL Resources

- Resource List: Children’s Play – More Than Fun and Games

Web Resources

-

National Toy Hall of Fame

Source: Strong National Museum of Play

The National Toy Hall of Fame recognizes toys that have inspired creative play and enjoyed popularity over a sustained period.

-

The Strong National Museum of Play

Source: Strong National Museum of Play

The Strong is a highly-interactive, collections-based museum devoted to the history and exploration of play.